|

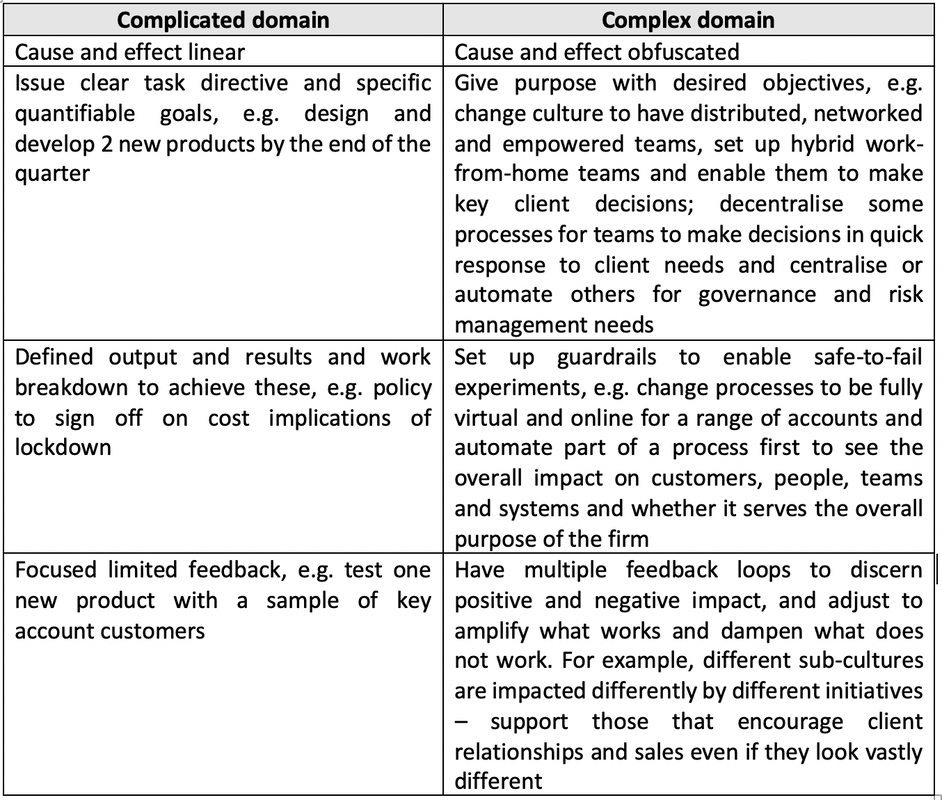

Even before COVID-19, the complexity that leaders faced was intensifying daily with the world becoming more connected and increasingly globalised while experiencing the rise of social media. Business leaders, in particular, were encouraged to embrace a broader vision than making profit (Hill, 2019), to be more responsive to matters such as global warming. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria needed to be included in asset manager portfolios as a measure for allocating financial investments (Economist, 2019). COVID-19 has since increased the level of complexity that leaders need to deal with in their decision making, illustrated by the impact that the pandemic has had on every sphere of society – political, economic, social, technological, environmental and legal. However, it is primarily a healthcare pandemic. It is causing considerable uncertainty and fear but also brings with it possibilities and opportunities in both South Africa and the rest of the world to create a post-COVID-19 world with new business, social and economic structures. The decisions leaders take in response to this pandemic will create the world of tomorrow and therefore they must take into account the long-term impact that their decisions will have on tomorrow. To enable decisions that will create the desired future, leaders will need to understand how complex systems work. Complex problems and systems are resultant from the numerous interactions within the network and thus cannot be individually distinguished; the system needs to be addressed in its entirety and cannot be addressed in a reductionist way; small inputs could result in disproportionate effects; problems that the system presents cannot be solved once and for all but instead require to be managed systemically, and any intervention tends to morph into new problems as a result of the interventions; and thus, relevant systems cannot be controlled and at best can only be influenced (Poli, 2013). Viewing the world and our current crisis through the lens of a complex system, one can observe the emergence of unintended and unforeseen patterns and behaviours that cannot be attributed to any of the constituents within the systems (Checkland, 1999) but must be taken into account when making decisions to address the challenges brought about by this crisis. This calls for a mindshift in decision making because a decision could present new challenges or the consequences of a decision could result in an unintended outcome due to the numerous interactions among the different elements within the network that cannot be individually distinguished. This results in a process of continual learning and improvement within the system. Ways to understand complexity The Cynefin framework, developed by Dave Snowden offers a useful frame to understand the underlying dynamics of a situation, to enable choosing a particular response which is most effective in that domain. Cynefin, pronounced ‘ku-nev-in’, is a Welsh word that signifies the multiple factors in our environment and our experience that influences us in ways we can never understand. The framework outlines five domains as ways of understanding the dynamics of a context based on the relationship between cause and effect. The domains are confused, clear, complicated, complex and chaos. By understanding the context, leaders can approach their decision making and problem solving in a way that matches the nature of that context. The domains on the right are ‘ordered’, meaning they contain knowable, solvable and predictable contexts. Starting on the bottom right, the ‘Clear’ domain contains obvious and simple issues and best practice can be applied to solve these matters. For example, if asked to produce a spreadsheet, this task is clear and straightforward. The spreadsheet may get more complicated as more factors are added but they are still answerable by an expert. Building a jumbo plane, for example, is more complicated process, but is still nevertheless solvable. Another example may be producing an annual integrated report. We can draw on the domains of experts, there are many stakeholders involved, and a number of iterations may be needed to produce the report but we do know the end output and can plan to complete this task. Moving to the left, the domains are ‘unordered’ in that the situations are unpredictable with various factors of the system interacting, so different scenes emerge with no clear line between cause and effect. One event can happen on one side of the world in a seemingly small wet food market and a global pandemic emerges. One person is murdered by a police officer that sparks global protests. This is complexity in an interconnected world. Businesses face many complex situations: the economy has declined, demand has been zero for our service for two months, the Reserve Bank has cut rates, the lockdown is looming, staff are required to work from home, our cash flow is stymied, etc. Should we retrench or not? Will demand increase and when? How will we need to organise the business for an unpredictable future? We may use many tools to assist us but the fundamental premise is that we simply do not know how our sectors and economies will emerge in the long term. Our best response in complexity is to probe and try various responses in the business and have multiple feedback loops to see which response best suits that context, and to grow those with positive trends. And the context shifts in complexity at an alarming speed, requiring ongoing responses to the multiple probes, such as trying new products in different markets, trying new organising principles for the business, trying new automation on part of a process. The chaos domain resembles crises and random events. As there are no constraints, what is needed is to primarily act to stabilise the situation. When COVID-19 first struck there was a call to stabilise the situation and clear communications came out to wash hands for two minutes , to maintain social distancing , to work from home – and a plan for five stages of lockdown was initiated, all in a quest to stabilise the situation. Once stabilised the context moves to the complex domain. We saw that the same rules did not apply to this domain. With the enforcement of lockdown level 5 and 4 the situation shifted and there was some backlash and resistance to the imposed rules. An adept leader reads the context and checks if constraints need to be reduced as they respond to a complex situation. Confusion may reign for a while and this domain in essence means that we do not know yet what is going on and where the context will go, so we may park some decisions until we are clearer of the patterns and implications in a complex situation. Leading in complexity means that we take multiple actions without knowing yet how they will all unfold. “Leadership is an improvisational art …. In the complex, fast-changing world we live in today, any ‘solution’ is just a temporary resting place, a park bench where you can pause and take a breath before getting back into the game” (Heifetz, Grashow & Linsky, 2009, p. 277). Good leadership requires openness to change on an individual level. Truly adept leaders will know not only how to identify the context they are working in at any given time but also how to change their behaviour and their decisions to match that context (Snowden & Boone, 2007). Leadership capacities that will support leaders to adapt and lead with greater ease and effectiveness in complexity are: · Sense-making · Systems thinking · Adaptability · Seeing multiple futures · Trying, probing, experimenting · Holding ambiguity and a ‘both/and’ mindset (rather than an ‘either/or’ mindset). The leader would therefore adopt different decision-making styles of leading and choices depending in which domain the context fits. The more effective style of leadership is inclusive with the leader listening to all perspectives, being curious and learning continuously, so the table below is for illustrative purposes only and not intended to be reductionist in thinking. Most leaders will feel most comfortable in the complicated domain that has been driven by our expertise, deep knowledge and often hierarchical approach. In the complex domain this insight is key, as is being open to multiple perspectives and experiments to explore which decisions and choices best match a particular decision or context. The way forward

A deep understanding of context, the ability to embrace complexity and paradox, and a willingness to flexibly change leadership style will be required of leaders who want to make things happen in a time of increasing uncertainty (Snowden & Boone, 2007). Leaders need to build their toolkit to work more aptly in a context of complexity and fast-paced change. This means that they need to enhance their capacities to understand the domain they are in and make decisions and respond to suit these complexities. Applying a complicated choice set on a complex domain may frustrate and achieve unintended consequences of greater disruption rather than control. Leaders need to listen to a broader range of perspectives to inform sense-making and build a broader network to enable a range of responses, both to experiment and receive more feedback. At the heart of this is building a more adaptable and flexible approach to contexts and holding ambiguity and a ‘both/and’ mentality. This does not mean inactivity; on the contrary, this means fast-paced and multiple responses, and then tracking what best serves the overall purpose and strategic direction of the firm. Leaders will also need to consider how they can build, upskill and structure their teams and organisations to work with complexity. Many a time complicated structures and processes have killed innovative ways to be agile in an ever-changing context. Leaders need to consider the lens through which they view complexity, learn to adopt these capacities with their teams, and consider which organisational processes and cultures allow for appropriate responses to flow. However, this does not negate that there is much complicated work to be completed and maintained. And this is where an astute leader learns to navigate between domains with greater ease and impact. Dr Gideon Botha CA(SA), Sarah Babb , [email protected] References Checkland, P. (1999). Systems thinking, systems practice. Chichester: John Wiley. Economist. (2019). What are companies for? Big business is beginning to accept broader social responsibilities. Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2019/08/22/big-business-is-beginning-to-accept-broader-social-responsibilities Heifetz, R.A., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009) The practice of adaptive leadership Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Harvard Business Press, 2009. Hill, A. (2019, 23 September). The limits of the pursuit of profit. Financial Times. Poli, R. (2013). A note on the difference between complicated and complex social systems. Cadmus, 2(1), 142–147. Snowden, D.J. & Boone, M.E. (2007). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, November 2007.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sarah Babb

Complexity means turbulence, but for leadership it is finding the flow in this. Archives

August 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed